On Saturday I spoke with my 92-year-old grandmother, Sheila Gebhardt. I called from inside my 550-square-foot studio in Phoenix, Arizona. It’s been my home for only six months. Grandma answered my call from the same Duarte, California house that she’s lived in since the ‘50s. Her three daughters grew up there, including my mom, who was the last to leave after graduating high school in 1979. My humble apartment is smaller in both size and history. But as our conversation elapsed, the differences in our geography and environment dissipated. We connected, or at least I felt that way, as she shared parts of her life story with me. That’s because so much of her history resonated with my own.

How much can a 30-year-old male have in common with someone who’s 62 years his senior? Well, more than you would think. For starters, Sheila and I have both been divorced. We’ve also both had nonlinear career paths. My grandma and I both went back to school to pursue a master’s degree and new vocation. I’m currently in the middle of that chapter in my life. I hope it ends the way hers did, with a cap, gown and employment.

But those commonalities between us just scratch the surface. We share an inner drive to pursue our goals, regardless of what others think. And both of our ambitions came with a cost. Sheila was motivated to have a career of her own, which wasn’t the norm in American society back then. A common view shared by her first husband, Chet Jelly.

“Well his mother was a slave to the men in your family,” grandma said, “and he thought that was how a wife should be. But I had other ideas.”

Chet didn’t agree with Sheila’s hunger to have responsibilities outside of their home. His lack of support didn’t stop with her work. Chet didn’t like that she had other interests, including politics. The issues eventually led to their divorce when my mother was in high school.

“I remember him saying to me one time. The reason he married me is because he thought I would keep a nice house for him and be a good cook. And he never mentioned that he loved me.”

Sheila divorcing her husband was also a taboo thing for that era.

“It was not socially unacceptable,” grandma said. “But it was, ‘Whoa, what has she done?’ Yeah, kind of looked at you a little sideways.”

In many ways she was ahead of her time. She was free thinking, career oriented, and unafraid to face the social ramifications of leaving a loveless marriage.

After hearing more about my grandmother’s uncommon ambitions, I couldn’t help but ponder my placement in today’s world. Unlike Sheila, some of my values and decisions are representative of a bygone era. I enlisted in the US Army after college in 2019 because I believed it was the right thing to do. Selfishly I craved the challenges and life experiences it would afford me. I thought that being a part of a special operations unit was the ultimate test of my character and masculinity. I needed to prove to myself that I was cut out for it and I didn’t want to look back later in life and regret being too scared to take that chance. Maybe my feelings were concocted from an outdated viewpoint of what it means to be a man. But it’s how I’m wired.

On a practical level I also thought joining the military was a way to be more useful. My decision ultimately stemmed from my desire to do something that mattered. Before enlisting I was an account executive for an advertising agency. My personality made me a good fit for client service work but I felt that I was capable of something more. I’m not saying my job wasn’t important, but I wanted to have more of an impact on others. Deploying to a foreign country to correct oppressive, bad actors seemed like the best way to contribute.

Eventually that’s what I did in the following years of my life. That decision hurt some of the people around me, particularly my first wife. Similarly to how Chet didn’t understand Sheila’s desire to have a purpose outside of being a wife and mother, Charlotte couldn’t conceive why I would want to give up my comfortable life. I had some good things going for me. She didn’t understand why that wasn’t enough or why I wanted to pursue the one line of work that would keep us apart for training and deployments. Charlotte never did. Our marriage ended shortly after my military career began.

Like any break up, the Army wasn’t the sole source of blame. I had my shortcomings as a husband. But it certainly was a friction point, for her and my family. I missed countless birthdays and holidays with my parents and sister during my time in the military. They sacrificed more than I ever did. I will never get that time nor those memories back. But when I was able to visit home, they were getting my best, true self because I was doing what I believed in. It’s a good feeling doing honest work.

Sheila felt the same way I did when she managed multiple part-time jobs while juggling motherhood. She became a licensed nurse after studying home economics at Rutgers University. Earning a degree wasn’t the pinnacle of her journey. Her diploma didn’t symbolize the end of having a life of their own like it did for so many other women back then who married their college sweethearts and became housewives. Now, there’s nothing wrong with being a homemaker. It’s an exhausting and righteous endeavor. And some couple’s situations require one partner to sacrifice their career for their children. But Sheila continued to work, because she needed to.

“I wasn’t content just to cook and clean,” grandma said. “I wanted to do other things.”

Having outside interests and goals mattered to Sheila more than what people thought of her. She blazed her own trail and faced obstacles along the way. Like me, she missed out on time with her family because of work.

“He [Chet] resented me not being home,” grandma said. “That I shouldn’t need to do something outside the house like that.”

At home Sheila was a dedicated mother and raised my mom and two aunts to the best of her ability. When she was absent because of her job the house never burned down. Although it almost did.

“I remember coming home one time,” grandma said, “and the girls had a little play house in the backyard. And one of the things they had was this little kerosene light. And somehow it caught the playhouse on fire. I was at work and I come home and the fire department has been here to put the fire out and I wasn’t arrested for child neglect. I think there would have been an investigation now [laughing].”

After two decades as a nurse, her desire to seek new challenges continued. Sheila went back to school at age 47 to pursue a master’s degree in nutrition from California State Los Angeles. This wasn’t an easy endeavor and required several sleepless nights studying after coming home from her shift at the hospital.

“I was working and going to school at the same time,” Sheila said, “and I often look back on those days. It was like being in prison because all I could do was work, eat and sleep and school. I remember studying for an exam one time and I had to coach myself to stay awake and I would feed myself little pieces of chocolate to stay awake and study.”

Despite having tired eyes, she pushed through and after two years eventually received her master’s of nutrition degree from Cal State LA.

“I don’t regret it,” grandma said. “I didn’t look at it as something that was too hard. It’s what I wanted to do.”

She worked as a nutritionist for Los Angeles County for 10 years before retiring. Before calling it a career, she helped create and improve many nutrition standards in state-sponsored institutions throughout the LA footprint.

“For the jails and schools I developed measuring tools for meals, school lunches and things like that,” Sheila said. “Because there were state standards, what was being fed to the students in the school lunches. So there had to be a way to see if they were meeting the standards. So that’s what the measuring tools did.”

Sheila also created teaching materials and courses for nursing clinics that educated them on the nutritional needs of their patients. The women she trained were mostly Mexican-American, so my grandmother had to learn some Spanish to teach. She had a spanish-speaking assistant alongside her that helped her just in case.

Her work was eventually implemented on a state level. Sheila often commuted 400 miles to Sacramento to demonstrate her measuring tools and education methods to the state board. She would rise at dawn to get to these meetings.

“Well, I guess I’m a goals person,” Sheila said, “and if I set my mind on doing something, I did what was necessary to get there. Nothing was ever, you know, impossible or too hard. I knew what I had to do and I did it.”

Like my grandmother, I sacrificed more than a few hours of sleep during my time in the service. During Ranger School I slept for three to four hours a night for 62 days straight. I led my squad on over 200 miles of patrolling on two or fewer meals a day. It really wasn’t that hard. But it sure did suck. I graduated the Army leadership course with a shaved-head and skeleton-like physique. But at least I had my Ranger Tab and was officially a part of my unit’s fraternity.

As my military career went on, the deployments dried up as a result of the United States’ changing foreign policy. The Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) pivoted to advising and supporting local partner forces. That meant my opportunities to participate in direct action operations became few and far between. Training for the Super Bowl every year becomes tiresome when you don’t get to play in the actual game. Besides, I was getting old and my 30th birthday was approaching. If I was to have a second career after the Army it was now or never in my eyes.

Over the last year of my service, I knew that I wanted to tap into my passion for sports while continuing to serve others when I left the military. I valued the social and cultural importance of athletics. Strangers and neighbors are connected by the passion for their team and the shared emotions of their successes and failures. I respected how reporters provide insight to their audiences and bring people closer to their teams. And in some cases, sharing stories that go beyond the field and inspire others. That’s why I enrolled in the Walter Cronkite School’s Masters in Sports Journalism Program at Arizona State University.

I’ve been a student at ASU for the last six months. In that time, I’ve dedicated myself to learning this new craft as fast as possible using the work ethic I inherited from Sheila and the military. Not because I’m an overachiever. But I have a short window to grow from a student into a professional over the three semester long program. To achieve this, I’ve sacrificed much of my personal life to meet Cronkite’s academic and student media standards. After many long nights spent writing and reporting, I’m getting there, but more work remains. The first semester and early days of my second term of school have been harder than I expected. Although I no longer have to get involved in physical altercations to do my job, being a journalism student has presented new types of pressures and worries.

But this time around, I have a partner that understands my goals. I married my beautiful wife Natalia last August, one day before starting school. Natalia is my support system and encourages me to keep fighting for my dreams. Since moving to Arizona together, she’s put up with more than any wife should. I’m away from her more often than not. My nights and weekends are often spent covering ASU hockey, basketball and now baseball. When I am home, I spend an indulgent amount of time watching and writing about the Anaheim Ducks of the NHL for a side job I have with The Hockey Writers. The time apart is difficult for both of us. But at least I am distracted by work. Luckily, she is stronger than me and continues to be my best friend through this new experience. This is the second time I’ve put my goals ahead of my relationship, but now I have an advocate who pushes me to the finish line and hopefully a new career like my grandmother.

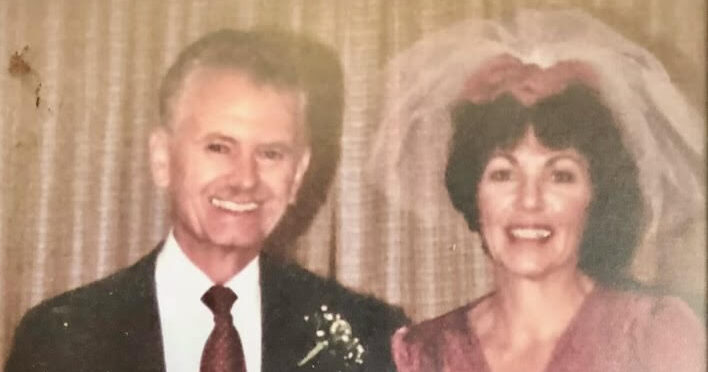

Sheila’s story had a happy ending too. And I’m not just talking about her successful second chapter as a state nutritionist. During her first job after graduate school, she met a new man at one of the courses she taught. His name was Carl Gebhardt.

“I had a class for the community at the health center I worked at in Pomona,” Sheila said. “And it was about diabetes and personal care for diabetes. Carl came to it. His mother was diagnosed with diabetes and he wanted to know more about it. And I’ll tell you as soon as I laid eyes on him I said, ‘He’s for me.’

Like so many times in her life, when Sheila wanted something she went after it.

“We would never have gone out together unless I had, you know, said something, called or contacted him,” grandma said. “I made up some reason for us to get together.”

The two remarried in 1980 and lived happily together for 40 years of marriage.

“Well, I guess intellectually Carl appreciated my accomplishments and what I was seeking,” grandma said. “Because I can remember telling Chet something that was very important to me and I wanted him to realize that. And he said, ‘If you think that then you must be crazy.’ Well, I mean, that’s no respect for my viewpoint, is it? No. Carl and I had mutual respect and appreciated what the other person was thinking.’

In her second union, Sheila finally had a partner that supported her ambitions and interests. Sounds familiar. The two went hiking together, discussed politics and traveled the world. They went all across Europe, but their favorite vacation was spent in Cairo, Egypt.

“I remember we had dinner in downtown Cairo,” Sheila said, “and we were sitting at this outdoor table in a restaurant and we were right by this outdoor oven. The bread that they had in Egypt, the women would roll the dough into two balls and then flatten them and put them on the side of the wall of this outdoor oven. And they would bake it against the wall of that outdoor oven, and then they pick them off and we’d eat them there. Oh god, I remember that being the best darn bread.”

Carl passed away on Aug. 17, 2020 but the memories and experiences they shared keep my grandmother at peace. Now Sheila lives alone in Duarte and has all the time in the world to put up with her grandchildren calling her. As we wrapped up our conversation, I contemplated how Sheila had both a successful second career and marriage – something I’m striving for right now. I asked Sheila if she had any advice for me.

“I never really gave out advice,” Sheila said. “So I can’t think of anything.”

Looking back, it was stupid question. My grandmother spent the last hour giving me all the answers I needed. Her story helped me in more ways than she knows. I should call her more often.