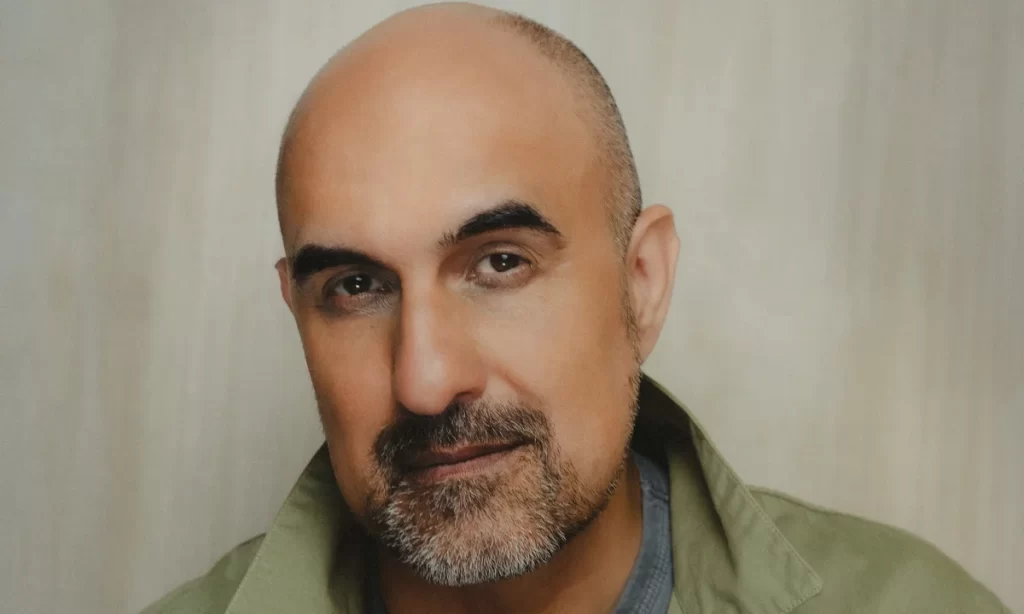

Blue Ruin by the renowned Hari Kunzru is the latest installment in the book club that my friends and I are desperately trying to make happen.

A book club for a bunch of twenty-somethings. Cliche and overdone perhaps, but we are trying, practicality be damned.

Blue Ruin serves as a commentary on the function and meaning of art, particularly in the ever-changing post-pandemic world. With no experience in post-pandemic literature and minimal understanding of the art world, I began the book enthused.

My enthusiasm slowly but surely waned as I got further into the book. What seemed to be revving up to serve as a commentary piece became a platform for Kunzru to flex his writing muscles.

It started so strong. The premise hooked me immediately: an old, grizzled artist who delivers food to barely make ends meet. On one delivery, he encounters a past girlfriend and a former friend and art school classmate, whom she left him for and is now married to.

From there, it was all downhill.

Unfortunately, Kunzru seemed unable to build on this premise, instead seeming to opt into pandemic stereotypes to fill the pages: a crazed, gun-wielding, conspiracy-spouting individual becoming a main character; constant quibbles about returning to the ‘big city’ from their remote location in the woods; conversations filled with bickering about the efficacy and safety of vaccines.

Perhaps I am not far enough removed from the pandemic and all of the lunacy that came with it, as these sorts of literary callbacks to that period filled me with dread and unease, which I do not believe was their purpose.

As a result, I struggled to connect to any of the notable characters.

I did not find myself invested in the idea of their development or rooting for them to succeed in any endeavor.

This lack of investment might have been because they were not wonderful people and had no issue telling the reader that, but I digress.

The further I got into the book, the more it felt like I was reading it for the prose on display rather than for genuine interest in the themes presented or the commentary Kunzru was attempting.

Beyond this, the window Blue Ruin offered into the art world, mainly through the lens of young art students trying to find their way, felt overdone and excessively cliche.

Pages upon pages of characters seeming to brag about living in squalor to have more money to rent studios. Drugs and alcohol galore, with the main character almost fueled exclusively by the duo.

I am open to the idea that I am just ignorant and that this is what art school is truly like, but it did not resonate with me or provide any unique insight.

Nevertheless, I soldiered on, harboring hope that the ending would provide a grandiose payoff.

This hope was misplaced.

A slow burn for the last few chapters ultimately led to nothing besides a realization for one of the flawed main characters that should have happened years ago.

Consequently, recommending this book to others is a dilemma.

I think those in and around the art world would enjoy it. The treks back into the main characters’ past, centered around their time in art school, would likely be a walk back down memory lane for that audience.

Besides that target audience, I would not recommend this book to others unless they are drawn to flawed characters who stay the same throughout a book and seem to exist solely to harken back to their younger days.

The most significant criticism I can give of Blue Ruin is that the book’s overarching theme and the structure and function of the book itself seem to be in direct contrast.

This broad criticism is an idea shared by Nate Hall, a fellow member of our illustrious book club, who put it best.

“This is going to sound so pretentious, but the book contradicts itself,” Hall said. “How are you going to talk about how art is about the act of creating it and not the dialogue surrounding it or the money you make from it by writing a very eloquent and artsy book that discusses art and ultimately generates money?”

In the end, while Blue Ruin attempts to explore topics that are foreign to me and that I am interested in, it feels disconnected from its own message. Kunzru seems to get lost in his abilities and, as a result, leaves me with much to be desired regarding character development or thematic payoff.

If a slow burn centered around the pitfalls of the art world and post-pandemic life is what you are after, then boy, do I have the book for you.

If not, perhaps another of Kunzru’s works is more up your alley. I know that is the case for me.